Today, we look at the first NBA team to have an all-Black roster.

This is “Don’t Got No Sports,” an occasional foray by me into a discussion about sports, which technically IS part of pop culture, but I’ll admit is very different from the stuff that I normally cover here, hence it receiving its own feature. Besides my pop culture and comic book writing, I also manage two sports blogs, one for the Yankees and one for the Knicks. So occasionally I’ll have something I feel like writing about sports.

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I thought it would be fun to take a look at the first time that an NBA game involved just Black players. It took a surprisingly long time for it to happen for a sport where Black players have been the majority of the league for many decades. And the reason it took so long was because of, well, you know, racism.

The first African-American players joined the NBA as play began in the 1950-51 season, the second season of the league following the merger of the National Basketball League and the Basketball Association of America in 1949. There were three African-American players that season, with Earl Lloyd of the now-defunct Washington Capitols technically being the first to break the color barrier (on account of Washington’s season opener being a day before the Boston Celtics and the New York Knicks, who each had an African-American player – Chuck Cooper on Boston and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton on New York). As the 1950s continued, more and more African-American players began being signed by teams, including some of the greatest players of the generation. From the 1955-56 season through the 1962-63 season, African-American players won six of the eight Rookie of the Year Awards. Five of those six players are currently in the Basketball Hall of Fame. However, while many talented African-Americans were joining the NBA, there seemed to be somewhat of an informal “quota” of sorts on how many African-Americans could be in the league at any one time. Entering the 1963-64 season, even while African-Americans were winning nearly all of the Rookie of the Year Awards and five of the last six Most Valuable Player Awards, no team in the league had more than four African-Americans on their team and many teams had less than four.

The 1963-64 season saw two notable changes. First, coming off of their fifth-straight NBA championship, the Boston Celtics became the first team to break the four-player quota by purchasing Willie Naulls from the San Francisco Warriors to go along with Sam Jones, Tom Sanders, KC Jones and the legendary Bill Russell (who was coming off winning his fourth MVP trophy). Second, later in the season the Celtics made history by having the first all-African American starting lineup (the aforementioned five players). The Celtics later made more history by hiring Bill Russell as their head coach in 1966.

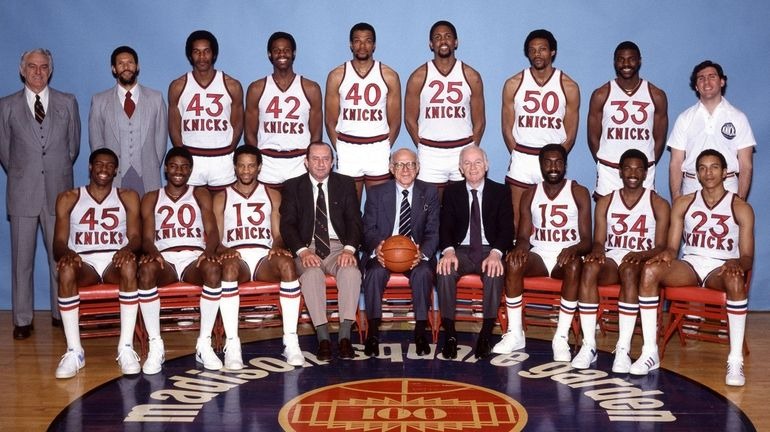

While more and more African-American players began to gain roster spots in the NBA as the 1960s went on, it was not until the American Basketball Association (ABA) debuted in 1967 that things changed dramatically. The ABA openly targeted African-American players and was also willing to sign players even if their college class had not yet graduated (something that the NBA would not allow). This advantage allowed them to sign a number of extremely talented players, including Artis Gilmore, George Gervin and Julius Erving. With the ABA breathing down the NBA’s neck, African-American players had greater leverage with their teams and by the early 1970s, the majority of the NBA player population was African-American. The percentage grew even higher when the ABA merged with the NBA in 1976. Still, even though the NBA was now predominately African-American, no team seemed to want to be the first one to be 100% African-American. That is, until the 1979-80 New York Knicks.

The Knicks had entered the 1970s on a high; winning their first NBA title in franchise history (they also saw their star center Willis Reed capture the first and still only MVP Award in Knick history for the 1969-70 season). They followed that up with a return trip to the NBA Finals in 1972 and 1973, with the latter resulting in the team’s second championship. By the end of the decade, though, injuries and age had robbed the team of nearly all of their star players. 1973-74 was the last season for both star forward Dave DeBusschere, key reserve Jerry Lucas and star center (and team captain) Willis Reed. The 1976-77 season was the last season in the NBA for star forward Bill Bradley. In addition, team leader Walt Frazier was traded to the Cleveland Cavaliers and legendary Knick coach Red Holzman retired after the Knicks finished the year 40-42. Only Earl “the Pearl” Monroe remained of the Knicks’ stars from that 1973 Championship team. Willis Reed returned to the Knicks to coach the team in 1977-78 as the team had sort of a last hurrah. The Knicks dealt for star center Bob McAdoo and went 43-39. They made it to the second round of the playoffs before being swept by the Philadelphia 76ers. The next year, though, things fell apart. Reed was fired after 14 games with Red Holzman coming out of retirement to return as head coach of the team. Holzman and Knick General Manager Eddie Donovan decided to rebuild following the team going 31-51 in 1978-79. McAdoo was traded to the Boston Celtics for a nice haul of draft picks, one of which was used to draft Bill Cartwright with the #3 pick in the 1979 NBA Draft. The Knicks were building around Cartwright and their top draft pick from the 1978 Draft, point guard Michael Ray Richardson.

Entering the offseason following the 1978-79 season, the Knicks, like many team in the league, had a pair of white players on the team. The players, rookie John Rudd and second-year guard/forward Glen Gondrezick were not major contributors to the team. Rudd barely played at all and Gondrezick averaged 20 minutes a game and contributed 5 points and 5.7 rebounds a game. Along with Cartwright, the Knicks were also adding two other first rounders, ninth overall pick Larry Demic and twenty-first overall pick Sly Williams. In addition, their second round pick, Reggie Carter and their third round pick, Geoff Huston, looked like they would stick with the team. When they signed free agent Hollis Copeland in August of 1979, there were just too many players left on the roster. Gondrezick was the last man cut on October 10, 1979, two days before the season began. The Knicks were now the first team in NBA history to have an all-African American roster. General Manager Donovan stated:

When it came down to our last cuts, Red and I felt we had to keep the best players. If we had kept Gondo and Rudd just because they were white, we would have lost the respect of our other players. The players know who can play and who can’t. I’ve had a couple of calls from fans about our decision but when I asked them if they would have wanted us to keep Gondo or Rudd as tokens, they said of course not.

The move brought mixed reactions from the Garden faithful. New York Post columnist Peter Vescey posted a number of letters from some angry fans and the Knicks’ roster move drew attention from all over the NBA. Even Willis Reed, when asked about the situation, said that he felt that the time was not yet right for an all-Black team, and that he personally would have kept a white player on the team. Things changed even more, though, with the fourth game of the season, as the 2-1 Knicks traveled to Detroit to face the 2-1 Pistons (then coached by Dick Vitale). In the October 18, 1979 game, history was made once again, as for the first time ever, all the players who participated in the game were African-American (the Pistons had one white player on their bench, rookie Steve Malovic). The players who played in the game were:

Knicks: Bill Cartwright, Jim Cleamons, Hollis Copeland, Larry Demic, Mike Glenn, Geoff Huston, Toby Knight, Joe Meriweather (who the Knicks had traded Spencer Haywood for), Micheal Ray Richardson, Ray Williams and Sly Williams

Pistons: Leon Douglas, Earl Evans, Roy Hamilton, Phil Hubbard, Greg Kelser, Bob Lanier, John Long, Jim McElroy, John Shumate and Terry Tyler

The Pistons would win 129-115 behind McElroy’s 31 points.

The Knicks would improve by eight games during the 1979-80 season, sniffing .500 at 39-43, but much was made at the time about how attendance in Madison Square Garden dropped by roughly 34,000 fans. This has been used over the years in a number of sports textbooks as a commentary about fan reaction to the Knicks having an all-African American team, and I always found that a weak argument. The Knicks were coming off of a 31-51 record! The drop-off from 1976-77 to 1978-79 was significantly higher (a reduction of roughly 80,000 fans) and, more importantly, in the 1980-81 season, the Knicks got back their lost attendance and then some, while still having an all-African American roster! So the notion that the fans did not come out to see the Knicks because they did not have a lone white player sitting on their bench is preposterous (oddly enough, after a 50 win season in 1980-81, the Knicks’ attendance dropped by over 100,000 people during the 1981-82 season, a season that they had two white players, Mike Newlin and Paul Westphal, on their way to a 33-49 record).

Here we are now over forty years later and the controversy that the Knicks dealt with in 1979 practically seems like it happened in an alternate universe. For instance, the sell-out crowds at MSG after the team traded for Carmelo Anthony trade sure did not seem to notice that the Knicks postseason roster that year consisted entirely of African-American players. No one wrote angry letters to Peter Vescey back in 1994 when the Knicks went to the NBA Finals with an all African American playoff roster. Fans just knew that they were watching good teams and at the end of the day, performance is what matters, not the color of the players’ skins.

Thanks to Dave Anderson of the New York Times for the great Donovan quote!