Today, we look at the first song to be recorded by a recording device so it could be played back.

In “When We First Met”, we spotlight the various characters, phrases, objects or events that eventually became notable parts of pop culture lore, like the first time that JJ said “Dy-no-MITE” or the first time that Fonzie made the jukebox at Arnold’s turn on and off by hitting it.

One of he most amazing things to me in the history of science are people like Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage who dealt with computers when there was inherently no way for them to actually make these computer ideas work. However, years later, more sophisticated devices COULD make their ideas work.

There’s a similar issue at hand when we discuss the first recorded song.

Thomas Edison developed the tin-based phonograph and in 1877, one of those tin foil recordings involved a clarinet solo…

Edison further developed the phonograph and in 1888, we got what is often thought of as the first recorded song, Handel’s “Israel in Egypt” recorded by an Edison associate, Colonel Gouraud, in England at the Handel Festivals, to demonstrate the utility of Edison’s phonograph cylinders…

Really, in a lot of ways, that IS the answer.

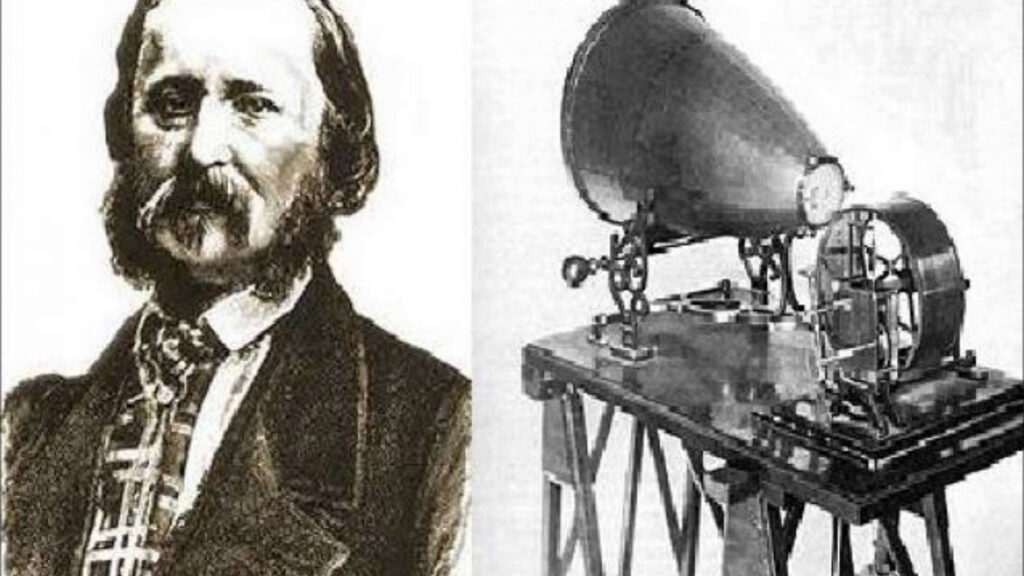

However, the “official” answer is a bit trickier. Like Lovelace and Babbage, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, a French printer and inventor, came up with a concept that was so far ahead of its time that it couldn’t actually be accessed until almost a 150 years after it was recorded!

Scott de Martinville thought that there was a way to record sound and so he invented the phonautograph, a device that would transform sound into written recordings. His intent was that we would be able to read said soundwaves, but that proved impossible. However, just like the grooves in a record contain sound that could be played back on a record player, so, too, could Scott de Martinville’s recordings be played back, they just couldn’t be played back BY HIM at the time.

Edison was once informed of Scott de Martinville’s work and he thought it was impressive, but at the same time, he though it sounded kind of pointless as what good was recording sound if no one could hear it played back?

Well, in 2008, Scott de Martinville’s recordings WERE played back and we can hear his April 1860 recording of the French tune, “Au clair de la lune”…

Fascinating stuff.

That’s it for this When We First Met!

If anyone has a suggestion for a future edition of When We First Met, drop me a line at brian@popculturereferences.com.