Today, I explain how there is a spectrum of scrutiny when it comes to pop culture changes.

This is the Cronin Theory of Pop Culture, a collection of stuff I’ve noticed over the years that I think hold pretty true.

As you may or may not know, when the Supreme Court considers the Constitutionality of a law, it typically used three levels of scrutiny – strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny and rational basis. The first one, strict scrutiny, is used in instances of specific “protected classes” are at issue (like race or religious belief). Here, the government has to prove that it has an extremely good and narrowly-defined reason for treating a citizen of a protected class different from other citizens. Intermediate scrutiny applies to less strictly protected classes, like gender or sex. Here, the government interest in the law must serve an important interest and violating the protected class must be substantially tied to the treatment of the protected class. Finally, there’s rational basis, which is for all cases involving non-protected classes. Here, the government just has to have any rational reason for passing a law. There’s typically always going to be SOME reason for a law being passed, so this is easy for the government to meet.

I think changes to pop culture also involve a spectrum of scrutiny. The more important the change is, the more scrutiny should be placed upon it. We sort of saw Marvel apply a version of this when it came to Captain America’s partner, Bucky, turning out to be alive. Editor Tom Brevoort required writer Ed Brubaker to give him a very compelling reason why the change should be made and Brubaker explained it well enough that Brevoort approved of the move, but an earlier writer who tried the move with a LESS compelling reason was turned down (Brevoort wasn’t the Captain America editor at that time, but he was asked his opinion of the move and he said it wasn’t a good enough reason to make such a major change).

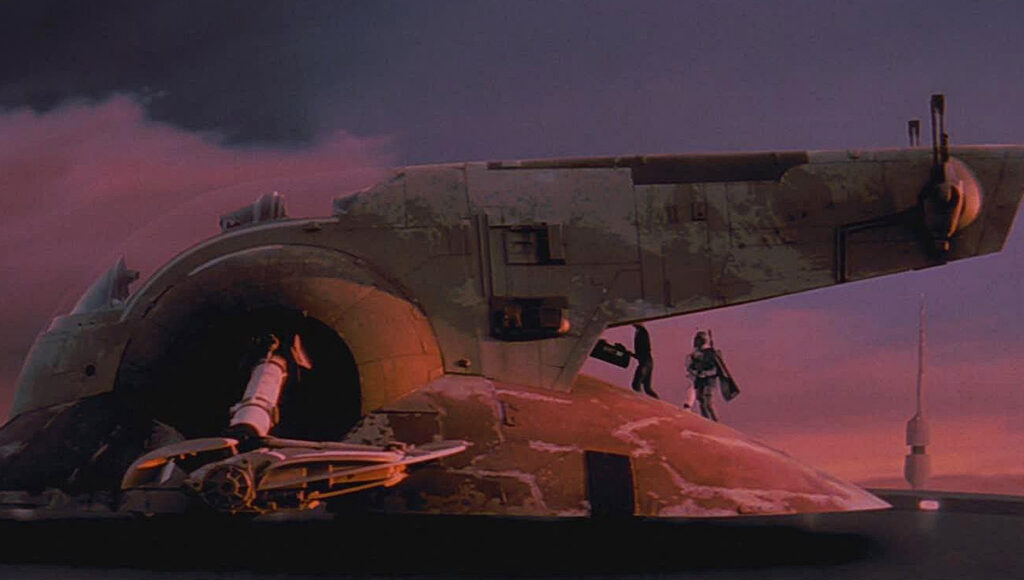

Therefore, when a change is minor, a company really just needs any sort of rational basis to make a move and I think “We don’t want to sell toys of a spaceship called Slave 1” is a good enough reason to make such a minor change as re-naming Boba Fett’s ship as Firespray (possibly not even technically re-naming it and more like calling the ship by the style of the ship, which is a Firespray ship, like having Luke call his X-Wing “an X-Wing”).

It stretched credulity for me to believe that anyone can be so invested in Boba Fett’s ship being called Slave 1 that this change angers them. I also find stuff like, “But it didn’t bother me as a little kid in the 1980s!” as a funny argument, similar to “Hey, if a 35-year-old White Guy came up with the name in 1979, how can we object to it now?”

Is the opposite true, and that it’s not that big of a deal that the ship WAS called Slave 1? Possibly, but, again, it’s such a small change that I don’t think there needs to be much of a reason given for it and simply, “We don’t want to sell toys for a ship called Slave 1” is more than enough for me.

I only ever knew the name of Boba Fett’s ship because of wikis, I don’t think the name was ever really a major element of the lore. There are some people who just love complaining about anything they perceive as being too “woke” no matter how insignificant.

The issue, I think, isn’t so much the renaming of the ship (I haven’t seen the show, but Firespray has been listed as its class before, so they could have just been referring to the class), but rather what the reasoning behind the naming might be. In the materials that would have named the ship, it was made clear that Boba Fett was a villain: he was ruthless, he betrayed people helping him, and there was the “no disintegrations” line from Vader that got explained. The name of his ship was a reflection of how awful of a person he was. If they’re trying to soften the character, then it would make sense to avoid the name Slave I or rename the ship.

I’ll still hang onto my Lego Slave I kit box.